Steve Keen’s Debtwatch No. 36 July 2009

It’s the Deleveraging, Stupid

Gentleman, you have come sixty days too late. The depression is over. — Herbert Hoover, responding to a delegation requesting a public works program to help speed the recovery, June 1930

“The past may not repeat itself, but it sure does rhyme” Mark Twain

In the last six months, the phrase “Green Shoots of Recovery” has entered the economic lexicon. It appeared to some observers that the global recession was coming to an end, while Australia itself was likely to barely feel its impact.

I would be as pleased as anyone if these “green shoots” were true harbingers of a genuine end to the economic downturn–not because I would enjoy being wrong for the sake of it, but because my expectations for the future are so bad that I’d prefer to see them not come to pass.

Unfortunately, on current data I expect that “green” is a better description of the knowledge level of those making the optimistic predictions, than of the colour of any budding economic recovery.

Of course, it could be argued to the contrary that many of those making such optimistic forecasts are highly trained professional economists, and not merely market commentators who migh have a vested interest in putting a positive spin on the news. This is true–but far from being a reason to trust these forecasts, it is yet another reason to be sceptical of them.

Almost every holder of a PhD in economics who works for a formal economic body like the Treasury, the RBA or the OECD has been deeply schooled in “neoclassical” economics, often without knowing that there is any other way of thinking about how the economy functions. They think they are simply “economists”, and anyone who objects to their analysis or models must be uneducated about economic theory.

In contrast, virtually all University Departments of Economics contain at least one economist who rejects neoclassical economics, and instead subscribes to a rival school–like Austrian, Marxian, Post Keynesian, or Evolutionary Economics.

These contrarian academic economists often disagree amongst themselves, sometimes vehemently–you couldn’t get two more opposed points of view than Austrian and Marxian economics, for example–but they tend to be united in regarding neoclassical economic theory as pompous drivel.

There are probably many reasons for this dichotomy between University economics departments which almost always have a handful of dissidents, and official economics bodies like the OECD and Treasury that are almost exclusively staffed by neoclassical economists. But I suspect the main reason is tenure: universities offer it, while formal economic advisory bodies don’t.

As a result, academic economists who “turn feral” and reject neoclassical economics can still teach and publish and hang on to their jobs, even if their neoclassical Department Heads wish they would go away. OECD and Treasury economists who do the same thing probably find their employment coming to an end–because they don’t have tenure.

So anything published by a formal economic body like the OECD will be the product of a neoclassical economic model–and therefore, in my opinion and that of a sizable minority of academic economists, drivel (there was one exception–the Bank of International Settlements [http://www.bis.org] while Bill White [http://www.bis.org/about/biowrw.htm], a supporter of Hyman Minsky’s “Financial Instability Hypothesis”, was its its Economic Adviser).

Of course, disputes between academic economists don’t matter in the real world, and most newspapers report the announcements of bodies like the OECD as statements of wisdom about the future–until, that is, a crisis like the Global Financial Crisis makes a mockery of the OECD’s neoclassical fantasies.

And what a mockery. This was the OECD’s forecast for the world economy in June 2007:

EDITORIAL: ACHIEVING FURTHER REBALANCING

In its Economic Outlook last Autumn, the OECD took the view that the US slowdown was not heralding a period of worldwide economic weakness, unlike, for instance, in 2001. Rather, a “ smooth” rebalancing was to be expected, with Europe taking over the baton from the United States in driving OECD growth.

Recent developments have broadly confirmed this prognosis. Indeed, the current economic situation is in many ways better than what we have experienced in years. Against that background, we have stuck to the rebalancing scenario. Our central forecast remains indeed quite benign: a soft landing in the United States, a strong and sustained recovery in Europe, a solid trajectory in Japan and buoyant activity in China and India. In line with recent trends, sustained growth in OECD economies would be underpinned by strong job creation and falling unemployment. (OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2007/1, No. 81, June 2007, p. 7)

Yeah, right. Instead the global economy was already well into the greatest economic crisis of the last 60 years. The next two years tore the OECD’s 2007 forecasts to shreds.

One might hope for some soul searching as a result of this–and hopefully some is occurring behind closed doors. But in a clear sign that the OECD hopes to see “Business as usual” restored in its modelling approach as well as the actual economy, its current Economic Outlook discusses the process of recovery from an economic crisis that it completely failed to foresee:

EDITORIAL: NEARING THE BOTTOM?

OECD activity now looks to be approaching its nadir, following the deepest decline in post-war history. The ensuing recovery is likely to be both weak and fragile for some time. And the negative economic and social consequences of the crisis will be long-lasting. Yet, it could have been worse. Thanks to a strong economic policy effort an even darker scenario seems to have been avoided. But this is no reason for complacency; the need for determined policy action remains across a wide field of policies…

In summary, it looks as if the worst scenario has been avoided and that OECD economies are now nearing the bottom. Even if the subsequent recovery may be slow such an outcome is a major achievement of economic policy. But this is no time to relax — ensuring that the recovery stays on track and leads towards a long-term sustainable growth path will call for major policy efforts going forward. (OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2007/1, No. 81, June 2009, pp. 5 & 7)

With its utter failure to see this crisis coming, why does anyone still take the OECD seriously? Probably for the same reason that people still generally obeyed the Captain of the Titanic after it had struck the iceberg: authority counts for a lot in a crisis, even if the person in authority actually caused it.

But it’s also because it takes repeated failures before someone who asserts authority is rejected–one failure alone won’t do. So rather like Napoleon in exile in Elba, the OECD is still taken seriously by economic commentators–as with Peter Martin’s report (“Late in, early out of the downturn”, SMH June 24th 2009):

AUSTRALIA is set to soar out of its economic downturn sooner and more sharply than forecast in the budget, according to forecasts from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development understood to have the backing of the Australian Treasury.

The OECD says the local economy should shrink 0.3 per cent this year, less than any other OECD economy and far less than the contraction of 1 per cent that underlies the forecasts in the May budget.

Next year the economy should roar back 2.4 per cent, also above budget forecasts and more than any other OECD economy apart from those recovering from collapse in 2009.

The Treasurer, Wayne Swan, greeted the forecasts released overnight in Paris as evidence Australia was “outperforming every other advanced economy in the face of the recession”.

The forecasts show Australia’s unemployment rate reaching 7.9 per cent late next year rather than the 8.25 to 8.5 per cent range assumed in the budget.

A little scepticism in this report would have been appreciated, given the OECD’s track record–and if a political journalist had written the report, that might well have occurred. But it was written by an economics correspondent, and most of them have–like the OECD’s economists–been schooled only in neoclassical economics, and don’t know how flimsy the theory itself is (there are exceptions here, like Brian Tookey whose book Tumbling Dice is an excellent critique of neoclassical economics). So we get a report like this trumpeting good times and green shoots, with no irony (Peter Martin was far from the only one to present the OECD’s views without any scepticism–see also “Earth-destroying bomb defused — just” by Michael Pascoe [http://business.smh.com.au/business/earthdestroying-bomb-defused–just-20090625-cxj7.html] or Glenn Dyer at Crikey “That’ s no green shoot, that’ s Australia in full bloom: OECD” [http://www.crikey.com.au/2009/06/25/thats-no-green-shoot-thats-australia-in-full-bloom-oecd/]).

Clearly it will take a few more economic failures before the OECD faces its Waterloo.

To be fair, official economic bodies and their uncritical fans were not the only source of “green shoot” euphoria. A large part of this feeling that the worst was over also came from the global experience of a recovery in stock markets from their recent lows. In addition, Australia had a near unique dose of greenery when unemployment remained remarkably benign, and it avoided the popular definition of a recession by recording growth in real GDP in the March 2009 quarter (real GDP rose by 0.4%, having fallen by 0.5% in the preceding quarter).

Let’s look first at the Stock Market.

The Dow has indeed had an impressive rally, from the low of 6547 on March 9 to the peak of 8799 on June 12–a rise of 34% in under a quarter of a year. This has led to many of the usual suspects proclaiming that the bear market is over, and a new rally is underway. Comparisons with 1929 are, of course, unjustified…

On closer inspection, reports of the death of the bear market are somewhat exaggerated.

Firstly, though the index has rallied by 34% from its low, it is still down 40% from the all time peak of October 2007.

Secondly, rallies like this came and went ad nauseam in the early 1930s, until the market hit rock bottom at 41.22 points on July 8th 1932–89% below the September 3rd 1929 peak of 381.17.

The biggest such rally occurred very soon after The Crash in 1929, starting on November 13th 1929 when the market was down 48% from its September peak. It then rose almost 50% from its low in under 6 months–and it was this recovery that inspired Hoover’s Oval Office gaffe.

But the market had only recovered half of what it had lost when the rally ran out of steam–a 50% fall followed by a 50% recovery still leaves you 25% below where you started from–and the inexorable slide of the Great Depression dragged the market down with it.

This current rally took a lot longer to start than its 1929 cousin, though it began from a comparable bottom (55% below the peak versus 48% below it in 1929), and it still has to go on for much longer and drive the market much higher to match its antecedent–let alone to proclaim the 2007 Bear Market is over (note also that Eichengreen and O’ Rourke, using global data, argue that the current decline is far worse than in the Great Depression, with global markets down 50% on average 12 months after the crisis versus just 10% down after 1929–see Figure 2 in http://www.voxeu.org/index.php?q=node/3421).

Meanwhile, in the Real World…

Though the stock market was providing some good cheer in the USA (at least until last week), the real economy continued to disappoint. To get an idea of just how bad the downturn has been, and how little inkling of it that conventional economists had, consider the Economic Report of the President, prepared by the US President’s Council of Economic Advisers (http://www.whitehouse.gov/administration/eop/cea/]), in 2008 (http://www.gpoaccess.gov/eop/2008/2008_erp.pdf) and 2009 (http://www.gpoaccess.gov/eop/2009/2009_erp.pdf).

The 2008 Report made the following forecasts–note in particular the “forecast” that unemployment would be below 5 percent between 2008 and 2013.

The 2009 Report, submitted to Congress and the incoming President in January of this year, made a mockery of the 2008 Report but still drastically underestimated the severity of the downturn: it forecast that unemployment would peak at 7.7% in 2009, growth would remain positive for the next five years.

Despite the frequency with which numerous economists who failed to anticipate the Global Financial Crisis continue to report sightings of “green shoots of recovery”, the actual economic data continued to be grimmer than even their most pessimistic revised forecasts.

The clearest evidence here is that the Federal Reserve’s “stress tests” for its Supervisory Capital Assessment Program assumed that even under an adverse scenario, unemployment would be below 9 percent by mid-2009. It is currently 9.4 percent (see http://4.bp.blogspot.com/_nSTO-vZpSgc/Siv54tjgl3I/AAAAAAAAGPo/7HhtUF998Q0/s400/unemployment+projections.png):

The tapering process that is built into neoclassical economic forecasts (see http://www.phil.frb.org/research-and-data/real-time-center/survey-of-professional-forecasters/2009/survq209.cfm) is not evident in the data to date.

Deleveraging and Economic Breakdown

The reason that most economists continue to underestimate this downturn is because (a) the downturn is being driven by deleveraging from literally unprecedented levels of private debt, and (b) the neoclassical theory of economics, which dominates academic and market economics alike, ignores the role of private debt in the economy.

The reason that I anticipated this crisis four years ago is that I reject the mainstream “neoclassical” approach to economics, and instead analyse the economy from the perspective of Hyman Minsky’s “Financial Instability Hypothesis”, in which private debt plays a crucial role. In our credit-driven economy, demand is the sum of GDP plus the change in debt. If debt is low relative to GDP, then its contribution to demand is relatively unimportant; but if debt becomes large relative to demand, then changes in debt can become THE determinant of aggregate demand, and hence of unemployment.

That is manifestly the case in America today. Under the stewardship of neoclassical economics in the personas of Alan Greenspan and Ben Bernanke, the growth in private debt has not merely been ignored but has actively been encouraged, in the dangerously naive belief that the private sector is being “rational” when it borrows.

This apparent indictment of the private sector as therefore “irrational” is in fact really an indictment of neoclassical economics for abuse of language. What neoclassical theory means by the word “rational” is “able to correctly anticipate the future”–which is the definition, not of rationality, but of prophecy.

There is nothing “irrational” about being unable to predict the future–it is fundamentally uncertain, while modern economic theory hides from this reality just as Keynes’s contemporary economic rivals did in the 1930s when he wrote that:

I accuse the classical economic theory of being itself one of these pretty, polite techniques which tries to deal with the present by abstracting from the fact that we know very little about the future. (Keynes, “The General Theory of Employment”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 1937)

Instead, in the uncertain world in which we live, the private sector necessarily speculates about the future–and some of those speculations will be wrong. The role of regulation and government economic policy should be to confine those speculations, as much as is possible, to productive pursuits rather than gambles about the future path of asset prices–a pasttime that has always in the past led to Ponzi asset bubbles.

This time, with government policy driven by neoclassical economics and its deluded attitudes towards the future, policy has actually encouraged the private sector to borrow to indulge in two giant Ponzi Schemes–the stock market and (belatedly) the housing market. It has gambled with borrowed money that share and house prices would always rise faster than consumer prices.

That gamble worked for some decades, but it then failed–in 1987–89. Had the Greenspan Fed not intervened then to “rescue” Wall Street, there is every possibility that the US would have experienced a mild Depression then–mild because the level of debt was lower then that at the time of the Great Depression (165% in 1989 versus 175% in 1929), and crucially because the rate of inflation then was high (5% in 1989 versus 0.5% in 1929).

The lower level of debt would have meant that less deleveraging would have been required to return to a predominantly income-financed economy in 1989 than was required in the 1930s, while high inflation would have meant a lower likelihood of deflation during the Depression itself, and possibly that inflation alone could have eroded the debt burden. It still would not have been pretty–certainly it would have been worse than the 1983 recession, when unemployment as it is currently defined peaked at 10.8 percent.

But what we face now will be far worse, because deleveraging from the now unprecedented debt level of almost 300% of GDP will drive America into a Depression that could easily be deeper than that of the 1930s.

This is already becoming apparent in the data, as economic historians Barry Eichengreen and Kevin O’ Rourke have pointed out (see “A Tale of Two Depressions” at http://www.voxeu.org/index.php?q=node/3421):

To sum up, globally we are tracking or doing even worse than the Great Depression, whether the metric is industrial production, exports or equity valuations. Focusing on the US causes one to minimise this alarming fact. The “ Great Recession” label may turn out to be too optimistic. This is a Depression-sized event.

The comparison of unemployment rates (which Eichengreen and O’ Rourke didn’t make) bear this out: using the current OECD definition of unemployment, this downturn is well ahead of the 1979 recession even though unemployment started from a lower level; and using the much broader U‑6 definition (see www.bls.gov; http://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.t12.htm), which is more strictly comparable to the NBER definition used during the Great Depression, unemployment now is as bad as at the same stage of the Great Depression, and increasing as rapidly.

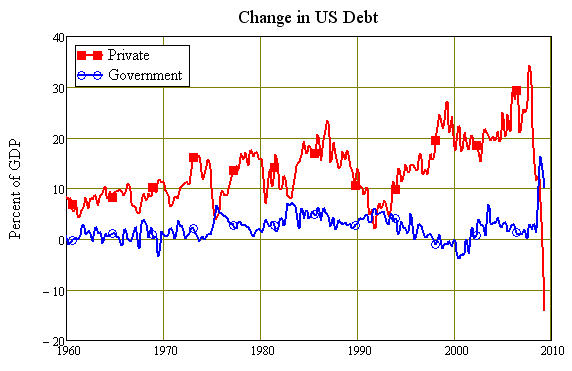

Deleveraging is already extreme: the most recent flow of funds data shows that private debt is falling rapidly and therefore subtracting from aggregate demand rather than adding to it. As noted in earlier Debtwatch Reports, in the modern debt-dependent economy, changes in the demand financed by changes in private debt are strongly negatively correlated with the unemployment: when debt’s contribution to demand falls, unemployment rises.

The turnaround in debt growth in the USA is unprecedented in the post-WWII period. Even during the 1980s and 1990s recessions, debt continued to grow both in nominal terms and as a percentage of GDP. Now debt is falling at arate of almost US$2 Trillion a year (which equates to 14 percent of GDP).

This is why the crisis exists, is so much worse than the official economic forecasters expected, and will continue and be much deeper than they currently believe: the crisis is being driven by deleveraging, and neoclassical economists do not even include private debt in their models.

As noted in earlier Debtwatch Reports, there is a very strong link between the rate of growth of debt and unemployment: when debt grows more quickly, unemployment falls; when debt grows slowly or falls, unemployment rises.

This is not because debt is a good thing, but because our economies have become so debt-dependent that changes in debt now have a far stronger influence on economic activity than do changes in GDP.

The US Government is attempting to “pump-prime” its way out of trouble by public-debt-financed deficit spending, which raises three further issues:

this so-called Keynesian remedy can work when private debt levels are relatively low, and government policy to attenuate private speculation is strictly adhered to (see my 1995 paper Finance and Economic Breakdown);

however, in our rampantly speculative economies, this policy has only worked when it has re-started the private debt binge, resulting in rising debt levels over time;

this can’t happen this time around, because all sectors of the private economy–businesses both real and financial, and households–are already debt-saturated. There is no “greenfields” group to lend to, as was possible in 1990 when household debt was a “mere” 60% of GDP, and the derivatives market in finance had yet to explode; and finally

the scale of the private debt bubble os just too big to be countered by substituting public debt for private debt.

This last point is evident in the data. Even though the US government has thrown the proverbial kitchen sink at government spending, the increase in public debt (which adds to aggregate demand) is more than counteracted by private sector deleveraging (which subtracts from aggregate demand):

Total US Debt is therefore falling. Though in the long run this is a good thing–we must return to a non-debt-dependent economy and once we have gotten there, stay there–the transition will be as pleasant as Cold Turkey is for a heroin addict.

“Gentleman, you have come sixty days too late. The depression is over.” — Herbert Hoover, responding to a delegation requesting a public works program to help speed the recovery, June 1930

“The past may not repeat itself, but it sure does rhyme.” Mark Twain

In the last six months, the phrase “Green Shoots of Recovery” has entered the economic lexicon. It appeared to some observers that the global recession was coming to an end, while Australia itself was likely to barely feel its impact.

I would be as pleased as anyone if these “green shoots” were true harbingers of a genuine end to the economic downturn–not because I would enjoy being wrong for the sake of it, but because my expectations for the future are so bad that I’d prefer to see them not come to pass.

Unfortunately, on current data I expect that “green” is a better description of the knowledge level of those making the optimistic predictions, than of the colour of any budding economic recovery.

Of course, it could be argued to the contrary that many of those making such optimistic forecasts are highly trained professional economists, and not merely market commentators who migh have a vested interest in putting a positive spin on the news.

This is true–but far from being a reason to trust these forecasts, it is yet another reason to be sceptical of them.

Almost every holder of a PhD in economics who works for a formal economic body like the Treasury, the RBA or the OECD has been deeply schooled in “neoclassical” economics, often without knowing that there is any other way of thinking about how the economy functions. They think they are simply “economists”, and anyone who objects to their analysis or models must be uneducated about economic theory.

In contrast, virtually all University Departments of Economics contain at least one economist who rejects neoclassical economics, and instead subscribes to a rival school–like Austrian, Marxian, Post Keynesian, or Evolutionary Economics.

These contrarian academic economists often disagree amongst themselves, sometimes vehemently–you couldn’t get two more opposed points of view than Austrian and Marxian economics, for example–but they tend to be united in regarding neoclassical economic theory as pompous drivel.

There are probably many reasons for this dichotomy between University economics departments which almost always have a handful of dissidents, and official economics bodies like the OECD and Treasury that are almost exclusively staffed by neoclassical economists. But I suspect the main reason is tenure: universities offer it, while formal economic advisory bodies don’t.

As a result, academic economists who “turn feral” and reject neoclassical economics can still teach and publish and hang on to their jobs, even if their neoclassical Department Heads wish they would go away. OECD and Treasury economists who do the same thing probably find their employment coming to an end–because they don’t have tenure.

So anything published by a formal economic body like the OECD will be the product of a neoclassical economic model–and therefore, in my opinion and that of a sizable minority of academic economists, drivel (there was one exception–the Bank of International Settlements while Bill White, a supporter of Hyman Minsky’s “Financial Instability Hypothesis”, was its its Economic Adviser).

Of course, disputes between academic economists don’t matter in the real world, and most newspapers report the announcements of bodies like the OECD as statements of wisdom about the future–until, that is, a crisis like the Global Financial Crisis makes a mockery of the OECD’s neoclassical fantasies.

And what a mockery. This was the OECD’s forecast for the world economy in June 2007:

EDITORIAL: ACHIEVING FURTHER REBALANCING

“In its Economic Outlook last Autumn, the OECD took the view that the US slowdown was not heralding a period of worldwide economic weakness, unlike, for instance, in 2001. Rather, a “ smooth” rebalancing was to be expected, with Europe taking over the baton from the United States in driving OECD growth.”

“Recent developments have broadly confirmed this prognosis. Indeed, the current economic situation is in many ways better than what we have experienced in years. Against that background, we have stuck to the rebalancing scenario. Our central forecast remains indeed quite benign: a soft landing in the United States, a strong and sustained recovery in Europe, a solid trajectory in Japan and buoyant activity in China and India. In line with recent trends, sustained growth in OECD economies would be underpinned by strong job creation and falling unemployment.” (OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2007/1, No. 81, June 2007, p. 7)

Yeah, right. Instead the global economy was already well into the greatest economic crisis of the last 60 years. The next two years tore the OECD’s 2007 forecasts to shreds.

One might hope for some soul searching as a result of this–and hopefully some is occurring behind closed doors. But in a clear sign that the OECD hopes to see “Business as usual” restored in its modelling approach as well as the actual economy, its current Economic Outlook discusses the process of recovery from an economic crisis that it completely failed to foresee:

EDITORIAL: NEARING THE BOTTOM?

“OECD activity now looks to be approaching its nadir, following the deepest decline in post-war history. The ensuing recovery is likely to be both weak and fragile for some time. And the negative economic and social consequences of the crisis will be long-lasting. Yet, it could have been worse. Thanks to a strong economic policy effort an even darker scenario seems to have been avoided. But this is no reason for complacency; the need for determined policy action remains across a wide field of policies…”

“In summary, it looks as if the worst scenario has been avoided and that OECD economies are now nearing the bottom. Even if the subsequent recovery may be slow such an outcome is a major achievement of economic policy. But this is no time to relax — ensuring that the recovery stays on track and leads towards a long-term sustainable growth path will call for major policy efforts going forward.” (OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2007/1, No. 81, June 2009, pp. 5 & 7)

With its utter failure to see this crisis coming, why does anyone still take the OECD seriously? Probably for the same reason that people still generally obeyed the Captain of the Titanic after it had struck the iceberg: authority counts for a lot in a crisis, even if the person in authority actually caused it.

But it’s also because it takes repeated failures before someone who asserts authority is rejected–one failure alone won’t do. So rather like Napoleon in exile in Elba, the OECD is still taken seriously by economic commentators–as with Peter Martin’s report (“Australia’s downturn to be shorter than expected”, The Age June 25th 2009):

“AUSTRALIA is set to soar out of its economic downturn sooner and more sharply than forecast in the budget, according to forecasts from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development understood to have the backing of the Australian Treasury.

The OECD says the local economy should shrink 0.3 per cent this year, less than any other OECD economy and far less than the contraction of 1 per cent that underlies the forecasts in the May budget.

Next year the economy should roar back 2.4 per cent, also above budget forecasts and more than any other OECD economy apart from those recovering from collapse in 2009.

The Treasurer, Wayne Swan, greeted the forecasts released overnight in Paris as evidence Australia was “outperforming every other advanced economy in the face of the recession”.

The forecasts show Australia’s unemployment rate reaching 7.9 per cent late next year rather than the 8.25 to 8.5 per cent range assumed in the budget.”

A little scepticism in this report would have been appreciated, given the OECD’s track record–and if a political journalist had written the report, that might well have occurred. But it was written by an economics correspondent, and most of them have–like the OECD’s economists–been schooled only in neoclassical economics, and don’t know how flimsy the theory itself is (there are exceptions here, like Brian Tookey whose book Tumbling Dice is an excellent critique of neoclassical economics). So we get a report like this trumpeting good times and green shoots, with no irony (Peter Martin was far from the only one to present the OECD’s views without any scepticism–see also “Earth-destroying bomb defused — just” by Michael Pascoe or Glenn Dyer at Crikey “That’ s no green shoot, that’ s Australia in full bloom: OECD”).

Clearly it will take a few more predictive and policy failures before economic journalists realise that with the global financial crisis, neoclassical economics–and hence the OECD–is facing its intellectual Waterloo.

To be fair, official economic bodies and their uncritical fans were not the only source of “green shoot” euphoria. A large part of this feeling that the worst was over also came from the global experience of a recovery in stock markets from their recent lows.

The Dow has indeed had an impressive rally, from the low of 6547 on March 9 to the peak of 8799 on June 12–a rise of 34% in under a quarter of a year. This has led to many of the usual suspects proclaiming that the bear market is over, and a new rally is underway. Comparisons with 1929 are, of course, unjustified…

On closer inspection, reports of the death of the bear market are somewhat exaggerated.

Firstly, though the index has rallied by 34% from its low, it is still down 40% from the all time peak of October 2007.

Secondly, rallies like this came and went ad nauseam in the early 1930s, until the market hit rock bottom at 41.22 points on July 8th 1932–89% below the September 3rd 1929 peak of 381.17.

The biggest such rally occurred very soon after The Crash in 1929, starting on November 13th 1929 when the market was down 48% from its September peak. It then rose almost 50% from its low in under 6 months–and it was this recovery that inspired Hoover’s Oval Office gaffe.

But the market had only recovered half of what it had lost when the rally ran out of steam–a 50% fall followed by a 50% recovery still leaves you 25% below where you started from–and the inexorable slide of the Great Depression dragged the market down with it.

This current rally took a lot longer to start than its 1929 cousin, though it began from a comparable bottom (55% below the peak versus 48% below it in 1929), and it still has to go on for much longer and drive the market much higher to match its antecedent–let alone to proclaim the 2007 Bear Market is over (note also that Eichengreen and O’Rourke, using global data, argue that the current decline is far worse than in the Great Depression, with global markets down 50% on average 12 months after the crisis versus just 10% down after 1929–see Figure 2 here).

Meanwhile, in the Real World…

Though the stock market was providing some good cheer in the USA (at least until last week), the real economy continued to disappoint. To get an idea of just how bad the downturn has been, and how little inkling of it that conventional economists had, consider the Economic Report of the President, prepared by the US President’s Council of Economic Advisers, in 2008 and 2009.

The 2008 Report made the following forecasts–note in particular the “forecast” that unemployment would be below 5 percent between 2008 and 2013.

The 2009 Report, submitted to Congress and the incoming President in January of this year, made a mockery of the 2008 Report but still drastically underestimated the severity of the downturn: it forecast that unemployment would peak at 7.7% in 2009, growth would remain positive for the next five years.

Despite the frequency with which numerous economists who failed to anticipate the Global Financial Crisis continue to report sightings of “green shoots of recovery”, the actual economic data continued to be grimmer than even their most pessimistic revised forecasts.

The clearest evidence here is that the Federal Reserve’s “stress tests” for its Supervisory Capital Assessment Program assumed that even under an adverse scenario, unemployment would be below 9 percent by mid-2009. It is currently 9.4 percent. The tapering process that is built into neoclassical economic forecasts is not evident in the data to date.

Deleveraging and Economic Breakdown

The reason that most economists continue to underestimate this downturn is because (a) the downturn is being driven by deleveraging from literally unprecedented levels of private debt, and (b) the neoclassical theory of economics, which dominates academic and market economics alike, ignores the role of private debt in the economy.

The reason that I anticipated this crisis four years ago is that I reject the mainstream “neoclassical” approach to economics, and instead analyse the economy from the perspective of Hyman Minsky’s “Financial Instability Hypothesis”, in which private debt plays a crucial role. In our credit-driven economy, demand is the sum of GDP plus the change in debt. If debt is low relative to GDP, then its contribution to demand is relatively unimportant; but if debt becomes large relative to demand, then changes in debt can become THE determinant of aggregate demand, and hence of unemployment.

That is manifestly the case in America today. Under the stewardship of neoclassical economics in the personas of Alan Greenspan and Ben Bernanke, the growth in private debt has not merely been ignored but has actively been encouraged, in the dangerously naive belief that the private sector is being “rational” when it borrows.

This apparent indictment of the private sector as therefore “irrational” is in fact really an indictment of neoclassical economics for abuse of language. What neoclassical theory means by the word “rational” is “able to correctly anticipate the future”–which is the definition, not of rationality, but of prophecy.

There is nothing “irrational” about being unable to predict the future–it is fundamentally uncertain, while modern economic theory hides from this reality just as Keynes’s contemporary economic rivals did in the 1930s when he wrote that:

“I accuse the classical economic theory of being itself one of these pretty, polite techniques which tries to deal with the present by abstracting from the fact that we know very little about the future.” (Keynes, “The General Theory of Employment”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 1937)

Instead, in the uncertain world in which we live, the private sector necessarily speculates about the future–and some of those speculations will be wrong. The role of regulation and government economic policy should be to confine those speculations, as much as is possible, to productive pursuits rather than gambles about the future path of asset prices–a pasttime that has always in the past led to Ponzi asset bubbles.

This time, with government policy driven by neoclassical economics and its deluded attitudes towards the future, policy has actually encouraged the private sector to borrow to indulge in two giant Ponzi Schemes–the stock market and (belatedly) the housing market. It has gambled with borrowed money that share and house prices would always rise faster than consumer prices.

That gamble worked for some decades, but it then failed–in 1987–89. Had the Greenspan Fed not intervened then to “rescue” Wall Street, there is every possibility that the US would have experienced a mild Depression then–mild because the level of debt was lower then that at the time of the Great Depression (165% in 1989 versus 175% in 1929), and crucially because the rate of inflation then was high (5% in 1989 versus 0.5% in 1929).

The lower level of debt would have meant that less deleveraging would have been required to return to a predominantly income-financed economy in 1989 than was required in the 1930s, while high inflation would have meant a lower likelihood of deflation during the Depression itself, and possibly that inflation alone could have eroded the debt burden. It still would not have been pretty–certainly it would have been worse than the 1983 recession, when unemployment as it is currently defined peaked at 10.8 percent.

But what we face now will be far worse, because deleveraging from the now unprecedented debt level of almost 300% of GDP will drive America into a Depression that could easily be deeper than that of the 1930s.

This is already becoming apparent in the data, as economic historians Barry Eichengreen and Kevin O’ Rourke point out in “A Tale of Two Depressions”:

“To sum up, globally we are tracking or doing even worse than the Great Depression, whether the metric is industrial production, exports or equity valuations. Focusing on the US causes one to minimise this alarming fact. The “ Great Recession” label may turn out to be too optimistic. This is a Depression-sized event.”

The comparison of unemployment rates (which Eichengreen and O’ Rourke didn’t make) bear this out: using the current OECD definition of unemployment, this downturn is well ahead of the 1979 recession even though unemployment started from a lower level; and using the much broader U‑6 definition, which is more strictly comparable to the NBER definition used during the Great Depression, unemployment now is as bad as at the same stage of the Great Depression, and increasing as rapidly.

Deleveraging is already extreme: the most recent flow of funds data shows that private debt is falling rapidly and therefore subtracting from aggregate demand rather than adding to it. As noted in earlier Debtwatch Reports, in the modern debt-dependent economy, changes in the demand financed by changes in private debt are strongly negatively correlated with the unemployment: when debt’s contribution to demand falls, unemployment rises.

The turnaround in debt growth in the USA is unprecedented in the post-WWII period. Even during the 1980s and 1990s recessions, debt continued to grow both in nominal terms and as a percentage of GDP. Now debt is falling at arate of almost US$2 Trillion a year (which equates to 14 percent of GDP).

This is why the crisis exists, is so much worse than the official economic forecasters expected, and will continue and be much deeper than they currently believe: the crisis is being driven by deleveraging, and neoclassical economists do not even include private debt in their models.

As noted in earlier Debtwatch Reports, there is a very strong link between the rate of growth of debt and unemployment: when debt grows more quickly, unemployment falls; when debt grows slowly or falls, unemployment rises.

This is not because debt is a good thing, but because our economies have become so debt-dependent that changes in debt now have a far stronger influence on economic activity than do changes in GDP.

The US Government is attempting to “pump-prime” its way out of trouble by public-debt-financed deficit spending, which raises 4 further issues:

- this so-called Keynesian remedy can work when private debt levels are relatively low, and government policy to attenuate private speculation is strictly adhered to (see my 1995 paper Finance and Economic Breakdown);

- however, in our rampantly speculative economies, this policy has only worked when it has re-started the private debt binge, resulting in rising debt levels over time;

- this can’t happen this time around, because all sectors of the private economy–businesses both real and financial, and households–are already debt-saturated. There is no “greenfields” group to lend to, as was possible in 1990 when household debt was a “mere” 60% of GDP, and the derivatives market in finance had yet to explode; and finally

- the scale of the private debt bubble is just too big to be countered by substituting public debt for private debt.

This last point is evident in the data. Even though the US government has thrown the proverbial kitchen sink at government spending, the increase in public debt (which adds to aggregate demand) is more than counteracted by private sector deleveraging (which subtracts from aggregate demand):

Total US Debt is therefore falling. Though in the long run this is a good thing–we must return to a non-debt-dependent economy and once we have gotten there, stay there–the transition will be as pleasant as Cold Turkey is for a heroin addict.